An American princess in London

This engraving is a portrait of Pocahontas (c. 1595–1617), created during her lifetime in England, by the artist Simon de Passe. It is one of the oldest works in the National Portrait Gallery’s special collection.

Pocahontas was a Native-American princess born before the founding of the United States. During the first Anglo-Powhatan War in 1613 she was kidnapped by English settlers of the Jamestown Colony, converted to Christianity and given the name ‘Rebecca’. In 1616 Pocahontas came to London and was exhibited by the sponsors of the Jamestown colony in an attempt to obtain money and encourage migration to the Americas.

The inscription on the portrait describes Pocahontas as ‘Rebecca’. It also states she is the ‘daughter to the mighty prince’, and the ostrich feather in her hand is a symbol of her royalty. Pocahontas died on a ship attempting to return to the Americas. She was buried in Kent. However, she has many descendants alive today living in America and Britain.

(Source information: the image has been provided courtesy of The National Portrait Gallery, London, ref: NPG D28135)

English settlement of Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown, England’s first permanent settlement in the Americas, was founded by the Charter of the Virginia Company of London, a firm. There were two ways of becoming a member of the Virginia Company: buying shares in the Company and remaining in England, or joining the Company as a planter. For service as a planter, the Company provided housing, food and eventually a share in the profits of the settlement in exchange for labour. This arrangement convinced some men from England to travel to North America to help establish the settlement at Jamestown in 1607.

These new English colonists learned very quickly that they were not colonising an empty land. The whole Virginia Colony, although claimed for England and named after Queen Elizabeth I – the ‘virgin’ queen – was part of a large Native American empire known as the Powhatan Confederacy. It was considered a confederacy because it was made up of dozens of large villages and settlements that paid tribute to a single leader, Wahunsenacawh, who was also known as ‘Chief Powhatan’. The Powhatans expanded their territory through a combination of war, intimidation, clever diplomacy and the trade of valuable objects.

During their first winter in the new settlement, between 1607 and 1608, the English colonists began dying of disease and hunger because they had not made adequate arrangements to find and grow food. They were forced to call on the help of the Powhatan people near the Jamestown settlement. Although the Powhatans viewed English colonists with suspicion, they initially tolerated the settlement because they benefited from trade with the new arrivals. In exchange for good relations and food, the English offered the Powhatans copper pots and iron fish hooks. The English colonists even tried to please Chief Powhatan by crowning him in a large ceremony of friendship, but he refused because Powhatan custom did not allow a chief to kneel before anyone other than a more powerful chief.

Relations between the English and the Powhatans were stable until the English, led by Captain John Smith, began to expand outside their fort at Jamestown. The English did this in an effort to remove their dependence on the Powhatans. Between 1609 and 1614 war between the English and the Powhatan Nation raged. But the English had failed to produce enough provisions for themselves; one Englishman was even executed for killing and eating his own wife.

Pocahontas as Lady Rebecca Rolfe: kidnap, marriage and conversion

The war ended in 1614 when a truce was agreed. This truce was symbolised in a marriage between the daughter of the Powhatan chief, Pocahontas (born ‘Matoaka’), who had been kidnapped by the English settlers as a tool to establish peace, and the colonist John Rolfe. Pocahontas converted to Christianity, had her name changed to ‘Rebecca’, and then travelled to England where she was exhibited around the English court as John Rolfe’s wife. Comments by people such as John Chamberlain, one of King James I’s courtiers, provide an insight into how she was received in the court. He saw the engraving of Pocahontas (in main source above), and wrote that it was ‘a fine picture but of no fair lady’.

The Virginia Company believed that if they could convert all of the Powhatans to Christianity it would help the survival and economic prosperity of Jamestown and so they paid for missionaries to travel from England to the settlement. In addition, after the mysterious disappearance of English colonists from Roanoke Island (c. 1590), some Englishmen wanted to promote the Jamestown colony, in contrast to Roanoke, as a success. Pocahontas, through her adoption of English customs and her conversion to Christianity, played a role in this.

Early expeditions and migrations

Pocahontas was not the first, nor the last, American to travel to England. Although Jamestown was England’s first permanent colony in the Americas, contact between English fishermen and the American far north pre-dated Jamestown by several hundred years – possibly even before Christopher Columbus’s first voyage in 1492.

Europe experienced booming population growth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and fish from Newfoundland helped to provide protein for the growing number of people. Fishermen from all over Western Europe converged on Newfoundland in the spring to catch and dry fish over the summer. They returned to Europe in the autumn with their cargoes. Fishing voyages kept to the coast and had no need of expensive permanent colonies. It was via these routes that the earliest American migrants arrived in England.

The Venetian John Cabot explored the coast north and south of Newfoundland on an English royal commission in 1497–1498, bringing several Americans back with him and presenting them to King Henry VII. One courtier, Robert Fabian, recorded his impression of them: 'These [people] were clothed in beasts skins, and did eat raw flesh, and spake such speech that no man could understand them, and in their demeanor like to brute beasts.' A couple of years later Fabian encountered them again 'in Westminster palace', and by then he could not tell them apart from all the Englishmen there.

In 1531, William Hawkins, who was carrying enslaved Africans to Brazil, returned to England with a man he described as a Brazilian king. He said the man was anxious to cross the Atlantic, and Hawkins left one of his own men behind in exchange. The Brazilian man was presented at the court of Henry VIII, and the courtiers all marvelled at the piercings in his face and upper lip.

In addition, Martin Frobisher led several expeditions to the far north of North America looking for a sea passage to Asia in the 1570s. On his first voyage, an encounter with native Inuits turned hostile and five Englishmen were seized. In return, Frobisher's men seized an Inuit man and took him to England, where he died after a few weeks. On his next journey, Frobisher's men seized a man named Calicough, and then a women, Egnock, and her baby.

People flocked to see the Inuits in England. When Calicough and Egnock landed in Bristol, the mayor held a party for them at his home. Calicough demonstrated his kayak on the Avon river, and brought down several ducks with his bird dart while he was paddling. John White painted Calicough and Egnock and her baby, and a Dutch painter, Lucas de Heere, painted the earlier migrant. Frobisher's backers sent a Flemish painter, Cornelis Ketel, to make several studies of Calicough and Egnock. Some of these were presented to Queen Elizabeth and hung in the palace.

Calicough and Egnock died a week apart after less than two months in England, and they were buried in Bristol. Dr Edward Dodding took care of Calicough, and performed an autopsy to determine how he died. Egnock's baby, Nutioc, was sent to London with a nurse, but died before he could be presented to the queen. He was buried alongside his countryman in the churchyard of St. Olave's, Hart Street.

Jamestown migrants in England

Pocahontas was not a lone migrant from Jamestown colony in the seventeenth century. Americans from Chesapeake Bay, where Jamestown was founded, went to England almost from the colony's beginning. Chief Powhatan accepted the gift of a thirteen-year-old English boy, Thomas Savage, and gave admiral Christopher Newport a young man named Namontack whose task was to learn as much as he could about England. Namontack travelled to England with Newport in 1608, and his presence created such a sensation that he was mentioned in a play by Ben Jonson, Epicene, or The Silent Woman. Namontack made at least two trips to England, and on one he was accompanied by another Powhatan man, Machumps.

Nanawack was sent to England by Jamestown governor Lord de la Warr in 1610 or 1611. Reports said that Nanawack had become a sincere convert to Christianity before he died at a young age. A little after Nanawack's arrival, Sir Thomas Dale sent several young Virginia Indian men to be educated in England.

In 1615 two more Powhatan men, Eiakintomino and Matahan, were in London. Eiakintomino was on display ‘in St. James Park in the zoo by Westminster before the City of London’, according to a note on the painting of him by a Dutch visitor, Michael van Meer (see: ‘Exhibiting Foreigners’ ). The struggling Virginia Company received royal permission to launch a national lottery so they could finance their colony, and Eiakintomino and Matahan were on the 1615 poster advertising the lottery, along with a portrait of James I.

When Pocahontas arrived in England in 1616, she was accompanied by an entourage, said to be ten or twelve people. The Powhatans' chief priest, Uttamattamakin, was in the party, and his presence was celebrated by London intellectuals, who listened to him as he described his people's religion over several evening meetings.

Other Americans in London at that time included Squanto, or Tisquantum, who had been captured along with twenty others on the Massachusetts coast in 1614 by a merchant named Thomas Hunt. Hunt took them to Spain to be sold as slaves but the Spanish government intervened and placed them with Roman Catholic priests to be educated. Squanto came to England with English merchants trading with Spain, and connected with merchants backing New England enterprises. They returned him to Massachusetts in 1619 and he acted as guide and interpreter for the separatist puritans known in American history as ‘The Pilgrims’. They settled in Squanto's home territory in 1620, the second successful English colony.

Many American migrants died soon after their arrival. The journey to England was long and arduous, and the English diet of the time was far less healthy than their own native foods. For one thing, because the water was so polluted, English people drank beer or wine with every meal, even breakfast, and, except in the summer, they ate food preserved in vinegar and/or salt. Most English people suffered from chronic low-level scurvy.

Nonetheless, American Indians continued to come to England, mostly for visits. In the later seventeenth century and beyond, some of them actually came on state visits as one set of rulers meeting another. And some came as part of famous entertainments such as Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Pocahontas: life and death in England

Unfortunately, like her contemporaries from the Americas, Pocahontas’s time in England was to be brief. During her time in the country she lived in several different places, including, Brentford, Middlesex (on a site where a Royal Mail sorting office now sits) and Heacham Hall in Norfolk. Whilst in London in 1615, she was reunited with Captain John Smith, the first English colonist with whom she had contact. Smith wrote that he was pleased she had become ‘very formal and civil, after our English manner’, expanding these thoughts in a letter to Queen Anne where he praised her for helping the Virginia Colony and referred to her as ‘the first Virginian ever spoke English, or had a child in marriage by an Englishman’.

Pocahontas’ life ended only shortly after John Smith’s letter to the Queen. In March 1617, she took ill on a ship bound for her homeland and died en route. She was buried in Gravesend, Kent where her body still lies.

Her burial record reads:

21 [March, 1616/1617] Rebecca Wroth wyffe of Thomas Wroth/ gent[leman] a Virginia Lady borne was buried/ in the Chauncell[i.e. chancel].

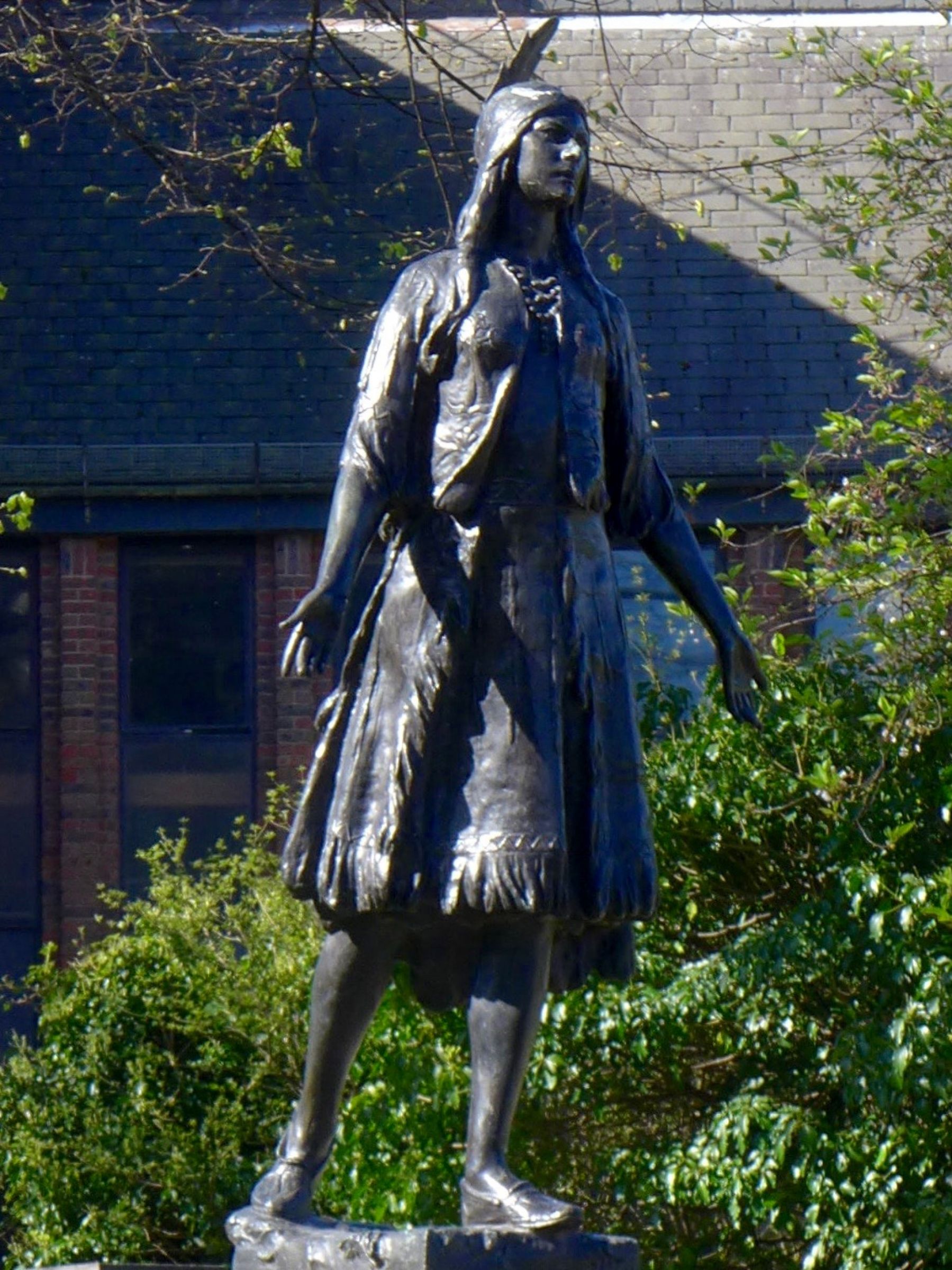

(Grade II life-size bronze statue of Pocahontas at St George’s church in Gravesend, Kent. Courtesy of St George's Church)

Note on terminology: The Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian poses the question: ‘What is the correct terminology: American Indian, Indian, Native American, or Native?’ Their answer is: ‘All of these terms are acceptable. The consensus, however, is that whenever possible, Native people prefer to be called by their specific tribal name. In the United States, “Native American” has been widely used but is falling out of favour with some groups, and the terms American Indian or indigenous American are preferred by many Native people.’

- Compare the engraving of Pocahontas above with the 1958 statue of her erected at St George’s Church in Gravesend (Kent). What are the similarities? What are the differences? Why might the artist who created the Gravesend statue have portrayed Pocahontas in such a way?

- While John Smith’s account of his rescue by Pocahontas is exciting, as noted here we now have reason to believe that ‘Smith was either making this story up, confusing it with a similar experience he had when he was captured by Turks in Hungary in 1602, or simply misunderstanding a ceremony to make him a Powhatan.’ What might Smith have had to gain if he did invent this story? As historians, what steps would we have to take to prove that this story is true or false?