Poems of protest: Meir ben Elijah and the Jewish people of early Britain

The Jewish community has deep roots and a long presence in Britain, but that history has not been without its challenges. This migration story's main source, a poem by Meir ben Elijah, reflects on the experiences of Jewish people in Norwich in the thirteenth century.

The translation of the poem is provided courtesy of Professor Susan Einbinder (Conneticut), and also appears in her article ‘Meir b. Elijah of Norwich: poetry and persecution amongst English Jews’, Journal of Medieval History 26:2, (2000).

Jewish people in early Britain: location, language, culture

Jews arrived in Britain with the Norman regime, following the Norman Conquest of 1066. It seems that during the reign of William Rufus (1087-1100) Jews were encouraged to migrate from Normandy, and support the government by offering financial services. Certainly, by 1100 a small Jewish community had been established, notably in London, and soon in other county towns and cities.

One of the early rabbis of London, Joseph, who worked during the period 1128-1130, came from Rouen, and this Normandy city would continue to be closely linked to the English Jewish community. The English Jews maintained close contact with other Jews in northern France and the Rhineland cities of northern Germany. Several cities, like Rouen and Mainz, were important centres of Jewish life and learning, and the English Jews remained in contact with the Jews living in them, through trade and marriage. They also had contact with the larger and sophisticated Jewish communities of southern Spain, then living under Muslim rule.

Connections with European Jews were maintained through travel: the famous Spanish-Jewish poet and philosopher Abraham ibn Ezra (died c. 1167) visited London in the 1150s, and visiting French Jews are known to have died in attacks on the Jews in London (1189) and York (1190). Books and letters moved between Jewish communities in Britain and the Continent, and we find several European Jewish writers referring to the British Isles as ‘the isles of the sea’.

English Jews were multilingual: they spoke English and French, and read and wrote in Hebrew for both religious and business purposes: their contracts were often written both in Hebrew and in Latin. Many of the English Jews had French names, such as Bonefey (‘good faith’ or ‘blessed’, the translation of the Hebrew name ‘Baruch’) or Dieulecresse (from the Latin ‘Deus cum crescat’, ‘God has added/increased’, itself a translating a Hebrew name such as ‘Joseph’ or ‘Gedaliah’). In other words, the English Jews were a cosmopolitan immigrant community, with strong European ties. They were embedded in British communities, and probably shared a great deal with the French-speaking Norman elite that governed the country and in particular, closely managed the Jews and their affairs.

Jews as servants of the Crown

By the thirteenth century, there were probably about 3,000 Jews in England, mostly concentrated in the county towns – like Lincoln, London, Norwich, Oxford, Winchester, and York – but they also spread out through the entire country, even reaching Wales. English Jews lived among their Christian neighbours, but they maintained their own places of worship, synagogues, ritual baths, and cemeteries. Remains of their communities can often be seen in street-names, such as ‘Old Jewry’ and ‘Jewry Street’ in London or ‘Jewry Street’ in Winchester, as well as in names such as the ‘Jews’ House’ at Lincoln, ‘Jurnet’s House’ (now a bar) in Norwich, or in the sites of Jewish cemeteries in Oxford (now the Botanic Gardens) and York. Jews did not live in ghettoes – as was the case elsewhere in later centuries - but like other ethnic groups at the time they lived in particular parts of towns, as their trade required, and to make social and religious life easier. They usually lived in rented properties, as there were restrictions on their ownership of land. The English Jews tended to live near the castles, which were centres of administrations, often the headquarters of sheriffs who managed the counties on behalf of the Crown. At times of danger Jews fled for royal protection in castles. In 1190 they fled to Clifford’s Tower in York, but their hopes were dashed when local knights had them burnt to death.

The Anglo-Jewish community was organised in a distinctive way. The Jews were not ‘subjects’ like other members of the population, but were rather ‘servants’ of the King. During the reign of Henry I (1100-1135), the Jews were issued a ‘charter of liberties’, which included the rights to move freely throughout the country, to have access to royal justice, and a special provision to ensure fair trial. In return for these privileges – which also made clear that the Jews were a separate group from their neighbours – the Jews were expected to exist to serve the King: they were answerable to him alone and were protected by his officials who also supervised and taxed Jewish property and income. The Jews were encouraged to lend money with interest, to rich and poor, to individuals and institutions, such as monasteries. In turn, the King benefited from their profits both by regular taxes and by occasional sudden requests for payments. Jewish officials managed the tax burden with community, and attempted to distributed it fairly among rich and poor Jews. The unusual economic position of the Jews at once meant that some of them were able to become extremely wealthy, but above all they were vulnerable. Yet they were confident enough on occasion to turn to the King for justice, even in cases that involved other Jews.

Concerning taking an inquisition. Order to the sheriff of Hampshire to inquire by the oath of twelve of the more law-worthy Jews of Winchester by their roll whether Cressus of Stamford, Jew, violently seized and took away the apple of Eve from the synagogue of the Jews in the same city to the shame and opprobrium of the Jewish community. If, by that inquisition, he shall be found guilty of that deed, then they are to distrain Cressus immediately by his rents, houses and chattels to give one mark of gold to the king for that trespass. Witnessed as above. By the king.

– From Henry III's Fine Roll

There was constant tension between the Crown and the Church over the treatment of the Jews: the Church wanted to force the Jews to pay tithes (taxes owed to the Church), to restrict the Jews’ finances (which they saw as a sin, ‘usury’), and, increasingly, church leaders sought to convert Jewish people. Under King Henry III (1207-1272) the church’s wishes were promoted vigorously, and houses for converted Jews in London and Oxford were founded. This long reign saw a transformation in attitudes to Jews, with greater impositions and heavier limitation on Jews’ work. It is not surprising perhaps that it was Henry III’s son – Edward I – in collaboration with the Archbishop of Canterbury together masterminded the expulsion of the Jews in 1290.

Jews in Norwich and the poetry of Meir ben Elijah

The medieval Jewish community of Norwich was not large but it was one of the most important in the country, Norwich itself being a leading trade centre. From it have survived some unique witnesses to the quality of Jewish experience in Britain. Most were involved in finance and trade, but some worked as artisans and tradesmen, and in medicine. Men also held important responsibilities within the community, as educators, prayer leaders, and officials in charge of care for the poor. Women were active in work, within household workshops, in domestic labour, and in moneylending too.

There are some unique traces of relations between Jews and Christians surviving from medieval Norwich. In 1150 a monk of Norwich developed an accusation that the Jews of the city had killed a local boy, William, some years earlier. The monk wrote a lengthy work in which he embroidered the imagined tale, which he claimed had taken place just before Easter and during Passover 1144. While there is no evidence of local violence, and he Jews were probably protected by the sheriff, the accusation became part of Christian traditions about Jews, and became current on the Continent too. In the 1230s, the Norwich Jews were accused of circumcising a local boy, and in the ensuing legal process a number of Norwich Jews were put to death; moreover, possibly as a result of this allegation, there was an attack on the Jews of Norwich by the city’s citizens in 1235, in which the Jews’ houses were set on fire and some of the Jews were beaten by the townspeople. Just three years later, in 1238, Jews’ houses in Norwich were once again set alight. It is clear that the King and his sheriff attempted to protect the Jews to some extent – as the Jews’ property was the King’s property – but local priests and the town sergeants, encouraged or allowed the violence. A few decades later, in 1278, local Jews were accused of forgery of coins, a crime considered a form of treason, and this led in 1279 to the imprisonment of many local Jews and at least five Jews were hanged and other Jews lost their property in the wake of these allegations. Such attacks took place increasingly in the later thirteenth century and form part of the background to the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290.

The rare survival of the work of a single poet, Meir ben Elijah, conveys some of the experience of such persecution and fear, in the life of a devout Jew. We do not know many biographical details about Meir ben Elijah, other than that he lived in the later thirteenth century and that his father was a rabbi. Meir styles himself as being from ‘Norgitz, in the isles called Angleterre’ and left us a remarkable and unique source in the form of a group of more than twenty piyyutim – poems of lament, written in Hebrew – that are preserved in ancient manuscripts.

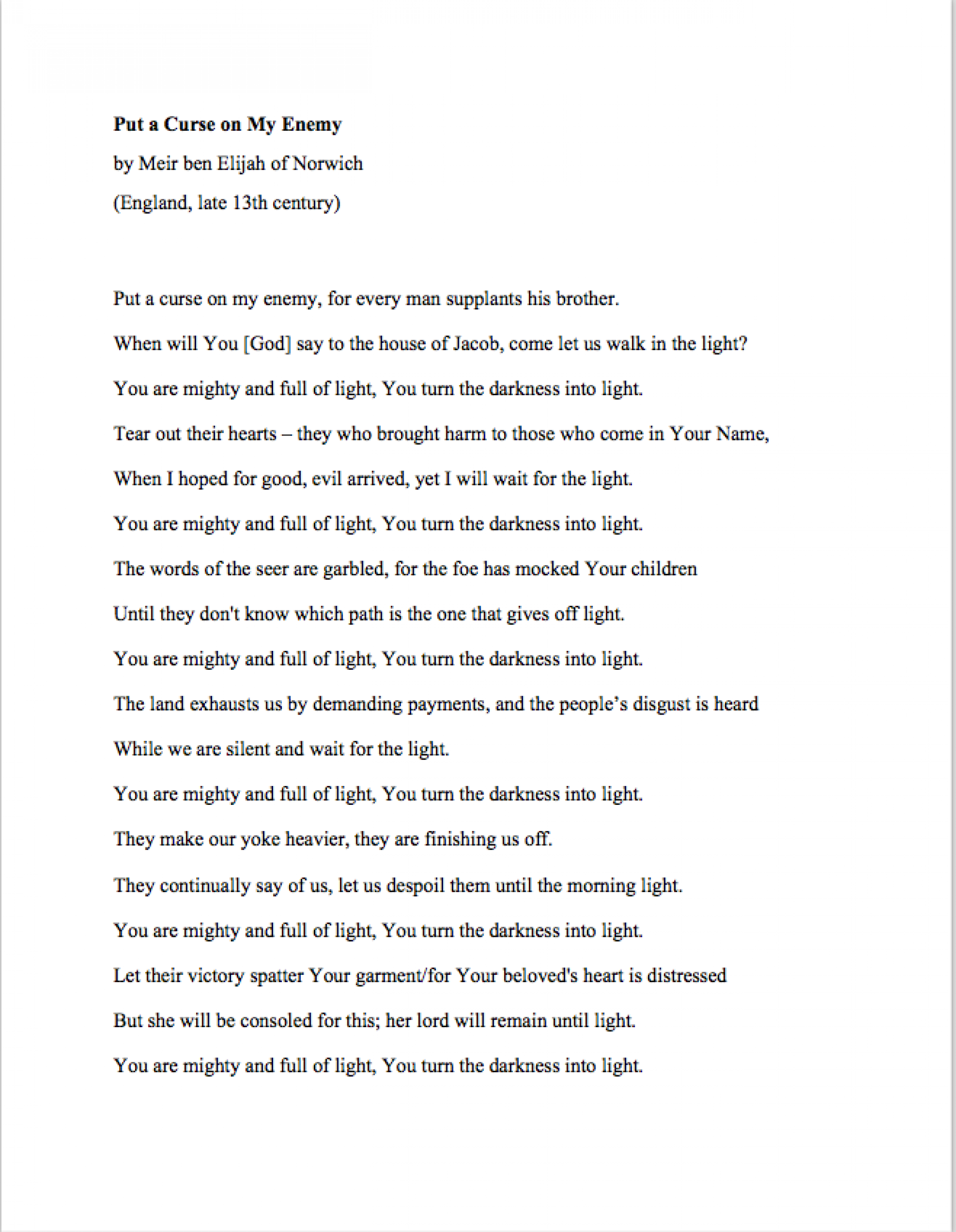

(PDF - 'Put a Curse on My Enemy', Meir ben Elijah, late 13th century. Translation courtesy of Professor Susan Einbinder, University of Conneticut)

Migrant testimonies: Meir's poem

The poem ‘Put a Curse on My Enemy’, might be seen as reflecting on the discrimination and persecution suffered by English Jews in the years leading up to their expulsion from England in 1290. The poem carries a heading that says that it is about ‘the heaviness of exile, the slayings in prison, and financial ruin’, and so reflects the recent experience of many British Jews. When Meir writes, in line 10, that the people’s disgust is heard, he may be referring to popular slanders and allegations about the Norwich Jews.

Meir’s poem is an eloquent attempt to combine the praise of God with the painful experience of the English Jews. The ‘darkness’ represents those who hate the Jews – apparently, local people and the authorities; the ‘light’ represents the Jewish God and the future Messiah, whom the Jews await. Meir’s poems survive in a unique manuscript now held in the Vatican Library in Rome; they were discovered in the 1880s by Abraham Berliner, and, whilst nothing is known about how they reached this particular archive, it is likely that the manuscript reached the Continent with one of the Jews expelled in 1290.

Meir’s poem is a rare example of a member of a migrant group attempting to ‘speak back’ to the majority group.

- How useful is the poem in giving us the Jews’ perspective on their experience as a migrant and outcast community in medieval England? Is poetry a useful response?

- What do you think caused Meir to write this poem, and who do you think this kind of poem was written for?

- How effective a response was the religious spirit of the poem – waiting for God’s help and for the Messiah – to the Jews’ declining fortunes in thirteenth-century England?’