Romani Gypsies in sixteenth-century Britain

The Egyptians Act 1530 was passed to expel people calling themselves ‘Egyptians’, and was not repealed until 1840.

Find below an extract from the original Egyptians Act 1530, followed by a translation:

'divers and many owtlandisshe people calling themselfes Egiptsions [who] using no craft nor faict of merchandise, have comen in to thys realme and goon from Shyre to Shyre and place to place in grete companye and used grete subtile and craftye meanys to deceyve the people bearing them in hande [persuading them] that they by palmestrye could tell menne and Womens Fortunes and soo many Tymes by craft and subtiltie hath deceyved the people of theyr Money & alsoo have comitted many haynous Felonyes and Robberyes to the grete hurt and Disceipt of the people that they have comyn among [...] the egipcians nowe being in this realme have maneag to departe w[ith]in xlii [fifteen] daies aftre proclamacion of this estatute among theam shalbe made upon payn of Imprisonnement ’

[a diverse and foreign people, calling themselves Egyptians, using no craft nor evidence of selling goods, who have come into this realm, and gone from shire to shire, and place to place, in great company; and used great subtlety and crafty means to deceive the people and persuading them that they, by palmistry, could tell men's and women's fortunes; and so, many times, by craft and subtlety, have deceived the people for their money; and also have committed many heinous felonies and robberies, to the great hurt and deceit of the people that they move among... the Egyptians who are now in this realm, have to depart within sixteen days.... and from now no Egyptians may enter the King's realm and if they do, then they with all their possessions, shall forfeit to the King our Sovereign Lord all their goods and titles and then must leave the realm within fifteen days under pain of imprisonment]

(Source information: the image of the Egyptians Act 1530 is provided courtesy of The National Archives, ref. HLRO HL/PO/PU/1/1530/22H8n9 (1530) and can be found here).

The Egyptians Act 1530 was a response to the arrival of Romani Gypsies, known as ‘Egyptians’ at the time, in Britain in the sixteenth century. The first definite record of these peoples in Scotland was in 1505, and in England in 1513 or 1514.

‘Egyptian’ migration to western Europe

The movement of Romani Gypsies to Britain in the sixteenth century must be understood in the context of the general migration of these peoples to western Europe from the fifteenth century onwards.

‘Egyptians’ were thought to have come from ‘little Egypt’, which was the name given to a part of the Peloponnese peninsula in what is now Greece. However, research from the late eighteenth century has shown that Gypsies with Roma heritage actually originated in northwest India. These people migrated from India through Persia and by the twelfth century had reached the Balkans in south-eastern Europe. The movement of early Gypsy groups was tied to expansions of the Persian, Seljuk and then Byzantine empires. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 was central to the establishment of Roma communities in what was to become one of their heartlands in Europe, the Balkans. In the Medieval period, ‘Egyptians’ became part of local life and culture right across the Balkans, and by the fifteenth century they started arriving in western Europe.Right across Europe, when groups of Gypsies arrived in a new city, they were initially welcomed by the local gentry and royalty. They were paid for playing music or telling fortunes and were given permission to camp, often on the outskirts of towns or just outside city walls. In the Scottish court in April 1505 there is a record of Gypsies being paid £7 at the request of the King, possibly either for providing entertainment to the court, or because they were thought to be pilgrims. Reports suggest that these early groups of Romani Gypsies carried papers with them certifying that they were pilgrims carrying out penance and asking for a guarantee of safe passage across the realm.

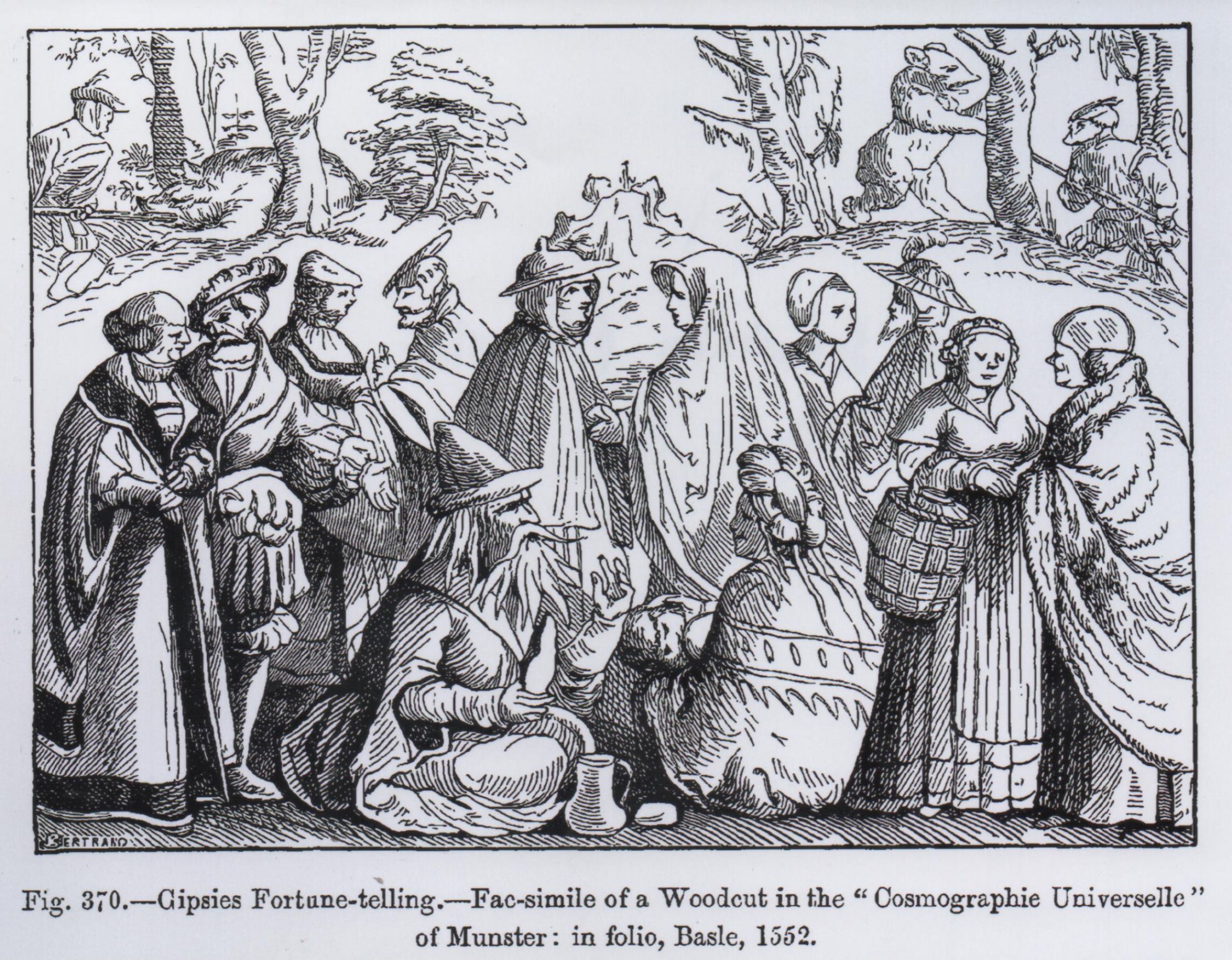

Gypsies Fortune Telling, woodcut in the Cosmographie Universalle of Munster, 1552, Basle (Courtesy of Robert Dawson Romany Collection)

Migration as part of everyday life

Romani Gypsies were just one of many groups of 'strangers' who the inhabitants of Early Modern European cities would have encountered. In the rapidly growing towns of Europe, movement and migration were a normal part of everyday life. By the fifteenth century, the transportation of goods had become quicker and easier and generally safer. Trains of pack animals were replaced by two-wheeled and then four-wheeled wagons, which were run by professional carriers and organised from a network of inns that provided warehousing and packing facilities. These changes in transportation were driven by expanding trade, which led to improvements in the widths and surfaces of roads and the building of countless bridges. Improved travel networks benefited travellers other than merchants and traders. There was a medley of moving people, including wandering scholars, minstrels and travelling entertainers, knife-grinders, travelling healers, hawkers and tinkers. Of course travelling alongside, and sometimes with, these groups, were pilgrims following well-trodden national and international routes to sites of religious importance. So, Romani Gypsies were, on the one hand, an exotic novelty in western Europe, able to find work as entertainers, and drawing crowds and audiences at courts because they were different. On the other hand, they were also part of a much larger population of travelling peoples in western Europe at this time.

Internal migration and vagrancy in Britain and western Europe

The arrival of Romani Gypsies in western Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries took place in the context of a rise in vagrancy across Britain and Europe. This was caused by a combination of declining real incomes, population growth (during the reign of Elizabeth I, the population rose from three to four million people) and bad harvests. Together, these problems caused food shortages, acute poverty and unusual amounts of migration. People in western Europe began moving to towns or other areas in search of work, and family groups and individuals took to living on the road, picking up work as they went. This movement led to the expansion of cities, social disruption in the countryside and in towns, and fears among the wealthy classes that chaos and violent unrest were a very real threat.

At the same time as this economic disruption and increased migration within western Europe, attitudes to poverty and the poor began to change. Unlike today, there was no definite support for people who were living in poverty. Traditionally people had turned to their church for charity in times of need and begging was seen as an acceptable way of life. However, the increasing number of paupers in the early sixteenth century put the church charity system under strain. Distinctions between the ‘true’ or deserving poor and the undeserving poor began to emerge. Orphans, the sick, infirm, aged or widowed were considered to be deserving of support. All those who were unemployed and who begged, other than those who were physically incapable of earning a living, were considered to be the undeserving poor. For the dominant classes, beggars and vagrants presented a profound threat to the established social order. In a period when the able-bodied poor were supposed to have masters, vagrants were ‘masterless’; they broke conventions of family, economic, religious and political life. Sixteenth-century vagrancy was about more than simply being poor, on the road and rootless. It is difficult to capture the meaning that terms like ‘beggar’ and ‘rogue’ held for contemporaries: today’s equivalent might be 'terrorist', 'extremist' or 'anarchist'. Edmund Dudley, writing in England in 1509, stated that vagrants were ‘the very mother of all vice…and the deadly enemy of the tree of commonwealth’.

The government tried to solve the problem of increased vagrancy in this period by attempting to outlaw vagabonds and ‘masterless men’. The most severe piece of legislation was Edward VI’s ‘infamous’ Act of 1547, which prohibited begging, sentenced vagrants to branding and two years’ servitude for a first offence, and execution for a second offence. The Egyptians Act 1530 (see main source above), like a number of other sixteenth-century laws, wrestled with the problem of separating the deserving from the undeserving poor and of controlling a potentially dangerous section of the population. Laws against Egyptians and the wandering poor, as well as laws to give the deserving poor support from their parishes, were passed across the second half of the sixteenth century – in 1563, 1572, 1576, 1597 and 1601.

Among those who were formally identified as the undeserving poor in these laws were rogues, beggars, vagabonds and, a new category, ‘counterfeit Egyptian’, which included people who were thought to be pretending to be Gypsies. In fact, historians now understand this latter category to be a combination of those, who had newly taken to a nomadic lifestyle as a result of the economic developments of the sixteenth century, and of Romani Gypsies, who were born in Britain. Despite such legislation, Gypsies born in Britain were not ‘foreign’, but British-born, and here to stay.

- In what way were ‘Egyptians’ like some other people in sixteenth-century Britain and Europe? In what ways were they different?

- In what ways were Europe and Britain changing at this time? How did these changes affect how Romani peoples were treated?

- Why might ‘masterless men’ have been seen as so threatening? Can you think of any other historical parallels?

- How does the treatment of ‘Egyptians’ compare to the way that other groups of migrants you are studying were treated?

- Have a second look at the extract from the Egyptian Act 1530, above. Is there any way we can group together the allegations? What is the overall worry of this section of the Act?