London on the move: West Indian transport workers

Ruel Moseley was one of over 4,000 men and women directly recruited by a London Transport employment scheme, which targeted workers from the British Caribbean. Ruel arrived in London from Barbados in 1959 to take up work as a bus conductor. Although he aimed to earn enough money to return home to Barbados after five years, Ruel ended up working for London Transport until he retired in the 1990s.

(Courtesy of London Transport Museum, Ref:1995/570)

From waterways to tube trains: transport workers in London

The development of London has been shaped by transport. From the days of Thames watermen in the 17th century, through to modern times and the advent of mass public transport by road and rail, transport workers have been an essential part of London life. Without them the capital would come to a standstill. The workforce has always reflected London’s changing population, but over the years different factors have influenced recruitment.

Over the last 200 years the staffing needs of the transport network have changed and evolved. The early underground steam railways and horse buses of the 19th century gave way to a growing electrified network of trains, trams, trolleybuses and petrol-engine buses in the 20th century. By the 1920s and 1930s, skilled and semi-skilled work in transport was highly valued and, before the Second World War, London’s transport system was considered the best in the world. London Transport (the integrated authority that ran the network) offered good wages and conditions of service, a uniform, free travel and access to a wide range of sports and social clubs. So jobs in transport attracted plenty of applicants.

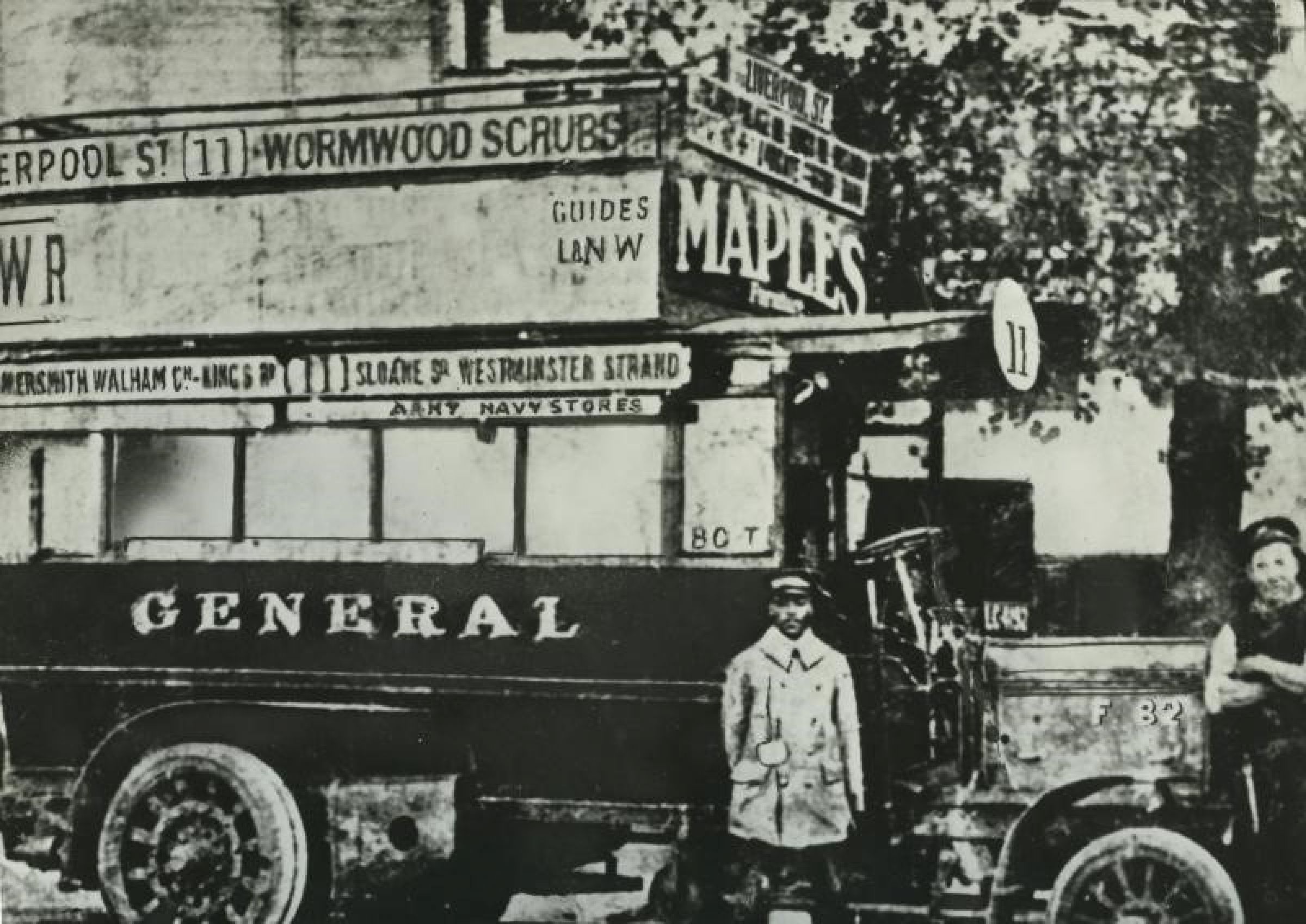

(Joe Clough, London’s first known black bus driver, in front of a London General Omnibus Company bus in 1910. He drove an ambulance in France for four years during the First World War. Courtesy of London Transport Museum ref. 2003/3519)

London Transport in the post-war years

From the late 1940s, however, London Transport experienced problems recruiting staff for semi-skilled front-line work. The expansion of the post-war British economy in the 1950s and 1960s resulted in new and better-paid job opportunities in light engineering, consumer goods and car manufacture. Rebuilding the bomb-damaged city also provided plenty of jobs in construction. In relatively stagnant sectors such as textiles, metal manufacture and public transport, wages fell. The long, anti-social hours and shift work in these industries also made the jobs less attractive. As a result, London Transport looked further afield for its workers.

London Transport began recruiting staff outside London in areas where unemployment was higher. This included the North-East of England and Scotland. During the early 1950s, the company extended the search to Ireland where it recruited both men and women to work on buses and trains. London Transport also provided temporary accommodation for new recruits.

Recruiting from Britain's colonies

In 1948 the Empire Windrush brought 492 Caribbean people to Britain, along with other travellers. These migrants arrived with British passports, as citizens, and were mainly from Jamaica. In the years that followed, increasing numbers of Caribbean people would make the same journey, following family and friends to seek work in Britain, including in transport.

Concerned with rising unemployment in Barbados, the Barbadian government eventually approached London Transport to set up a more formal arrangement for recruitment. In 1956, London Transport became the first organisation to operate a scheme recruiting staff directly from the Caribbean. Between 1956 and 1970, thousands of new recruits came to London from Barbados to work for the network. For a short period in 1966, applicants came from Jamaica and Trinidad as well.

The recruitment scheme became a model for other large public-sector employers, such as British Rail and the National Health Service (NHS) (see: 'Sailing from St. Vincent: the story of Jannett V. Creese'), which also became major recruiters. A small number of bus drivers were also recruited from Malta in 1965. As residents of a former British colony, Maltese workers were targeted because they drove on the left-hand side of the road, as in the United Kingdom.

How did London Transport's recruitment scheme work?

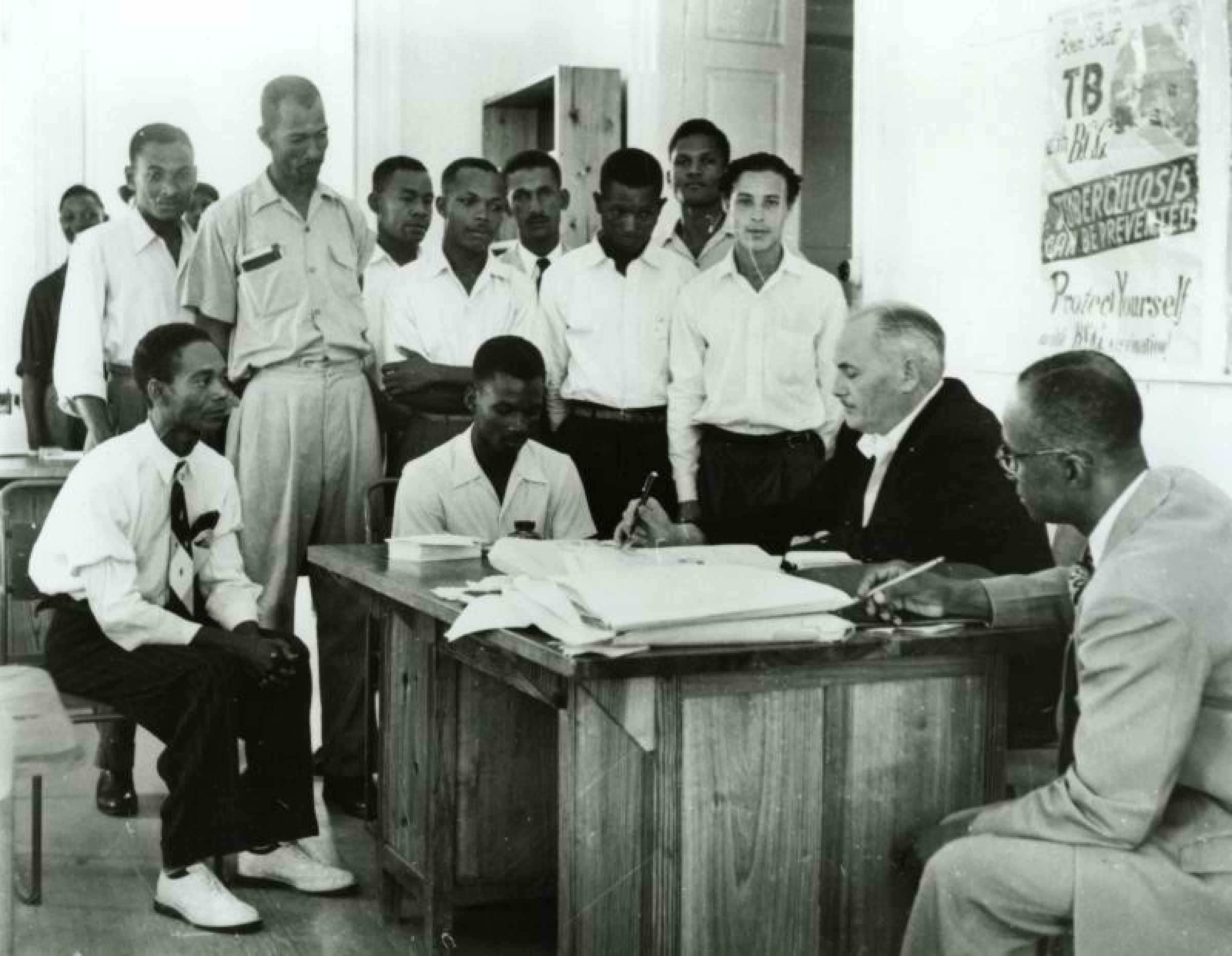

The London Transport Establishment (Human Resources) Officer, Charles Gomm, set up a recruitment office in Bridgetown, the capital of Barbados. Information about the London Transport scheme appeared in local newspapers and poster campaigns and was advertised on the radio. Recruitment began to happen on a regular basis and it became common knowledge amongst the island's small population. Applicants from Barbados recall being interviewed and answering a long list of questions, after which they were required to pass a written test and a medical before being taken on.

(Charles Gomm, Recruitment officer for London Transport, with some early applicants in Barbados, 1956. Courtesy of London Transport Museum, ref. 1998/83757)

The majority of those hired were male, but women were also taken on to become bus conductors, station staff and canteen workers. London Transport’s policy was to only employ single people, not couples or families. In reality, a number of Barbadian recruits were already parents and many children were left behind to be looked after by grandparents and other family members.

Single mothers described difficulties in bringing their children to join them in Britain, for reasons including financial difficulties, long hours and red tape. As with other similar recruitment schemes run by the National Health Service and British Rail, the Barbados government lent recruits the fare to travel. This was then paid back over two years.

(Woman bus driver training at Chiswick works in the 1970s. Courtesy of London Transport, ref. 2014/8404)

London Transport's direct recruitment schemes from the Caribbean continued until 1970, by which time the Commonwealth Immigration Acts of 1962 and 1968 – which were designed to limit immigration to Britain – had reduced the numbers of Caribbean people arriving. Nevertheless, over 4,000 workers from the Caribbean were recruited onto the scheme.

Not all transport workers from the Caribbean came to Britain through organised recruitment schemes. Some also made their way independently, and applied directly to London Transport for operational jobs on the buses and trains. They also filled other roles, such as track maintenance and construction work.

Pay and working conditions for Caribbean recruits

Basic pay for station staff was £7 10s for a 44-hour working week. The amount printed in larger text on the poster, £9 9s 2d, was for basic pay plus overtime work and enhanced payments for unsocial hours. The hours staff worked, and the payments they received, were strictly regulated and agreed with the trades unions. Jobs on the buses offered similar, but slightly lower, wages. All staff received something less than the national average pay at the time, which was around £11 10s.

On both the Underground and the buses, women were paid less than men for the first six months. As in London today, a large part of workers’ wages had to be set aside for rent and other bills. This didn’t leave much for leisure or savings.

Labouring on the Underground and buses involved shift work, which meant staff might work up to 12 days out of 14. An morning shift could start as early at 5 a.m, and an afternoon shift could finish as late as 1 a.m. Some duties entailed staff working during both the morning and evening peak periods, which meant it could be 12 hours between the start and end of their day.

Case study: Ruel Moseley, bus conductor

One of the recruits on London Transport's scheme was Ruel Moseley from Barbados (see passport photo above). In Barbados, Ruel worked as an apprentice to a tailor and then as a conductor on the local buses, before successfully applying to work for London Transport at the age of 25.

In 1959, through the recruitment scheme, Ruel acquired his first British passport and left Barbados on a ship that took four weeks to reach England. Later in the 1960s recruits were often booked on flights to London, so their journey was much quicker.

Training for new starters began immediately on arrival. Although Ruel had some previous transport experience in Barbados, it was in a small town and on country runs, often on poorly maintained roads. This made the transfer to the hustle and bustle of London and its traffic difficult. One of Ruel's colleagues at London Transport recalled having just a week’s training in the classroom, followed by a week on the road, to get used to the unfamiliar system and a new currency.

Ruel worked as a conductor first on the trolleybuses, and later on buses at Hanwell garage in west London. Like many of his colleagues, Ruel originally planned to stay in London for about five years before returning to Barbados. But a combination of factors, including raising a family, led to him to stay and work for London Transport until he retired in the 1990s.

Building a life in London

The late 1950s, when Ruel arrived, was a time of racial tension in Britain. Black workers, along with other ethnic minorities, experienced many challenges. Work was hard and finding accommodation was challenging, as many recruits faced racial discrimination.

Talking about poor living conditions in London Ruel Moseley said, ‘You were not used to sharing five to a room. However poor you were in Barbados you were not used to sharing a room. You had to be in work by 6.30 am. You had to keep your dignity ... you had to keep working... A lot of boys came here and had mental breakdowns because of that stress.’

Communities began to build within churches, sports clubs and ‘blues dances’ as places for socialising and support. London Transport had an established tradition of supporting sports clubs, societies, social events and competitions for employees. Many of the Barbadians, with their well-known cricketing tradition and skills, were in demand in both neighbourhood and corporate teams.

As a young man Ruel Moseley played for the London United Tramways cricket team from 1959 to 1967, and later the Central Road Services (CRS) cricket team. The CRS team had an enviable reputation and were unbeaten in tournaments for 26 years. Even then, they were only beaten by the Birmingham transport team, which was also made up of Caribbean, mainly Barbadian, players.

Those who remained with London Transport slowly got promoted within the company, but only after campaigns by the West Indian Standing Conference and the Campaign against Racial Discrimination, which highlighted the fact that these workers were being treated unequally. It appeared that London Transport had only expected recruits to fill basic roles before moving on or returning home. Instead, many stayed on to play a crucial part in running the transport system.

(London Transport Central Road Services cricket team celebrating victory in 1984. Courtesy of London Transport, ref. 2006/15877)

London transport today

Over the years, changing travel patterns and technological advances have meant that fewer staff are needed to run London’s public transport. In 1956, London Transport had a staff of 87,000. In 1968, the company had 73,000 employees, of whom 9,000 were estimated to be black. By the end of the twentieth century there were fewer than 35,000 staff.

London in 2017 is an ethnically and culturally diverse city where 300 languages are spoken and over 14 faiths are practised. Within Transport for London – which was created in 2000 as the successor to London Transport – the workforce includes new generations of black Londoners, some of whom are children and grandchildren of the first Caribbean recruits.

(Peckham bus garage staff social event, around 1960. Courtesy of London Transport Museum ref. 1999/9477)