Resisting racism: the Bradford 12 defence campaign

From South Asia to Bradford

In the 1950s and 1960s South Asians from India and Pakistan (including East Pakistan, which would later become Bangladesh) were welcomed to Britain to work in the mills and factories of towns across Yorkshire and Lancashire. Bradford had the highest concentration of South Asians compared to other towns. In 1964 there were approximately 12,000 Pakistanis in Bradford; by 1970 this figure had increased to 21,000. South Asian migrants in Bradford mainly worked in the wool and engineering industries. Many of the migrants came from rural areas of Northern Punjab as well as from Mirpur in Pakistan. Others were from Indian Punjab as well as elsewhere in the subcontinent.

The process of migration involved de-classing for most Indian and Pakistani families who, before migrating, had often been involved in middle-class or lower middle-class professions. Some had been teachers, business people or army personnel. In England the only jobs they could get were in factories. When the children of these first-generation migrants grew up, they had dreams and aspirations but had witnessed their parents pushed back from achieving their dreams through racism in the housing and job market. Racism in education had limited the prospects of many in the second generation: many were bussed to schools outside their own areas, leading to increased bullying and violence, and were also often placed in 'English as a second language' streams, where they were unable to access the full curriculum and therefore often left school with low levels of qualifications.

The birth of the Asian Youth Movement (AYM)

Britain’s industrial decline in the 1970s also led to an increase in racist violence on the streets, including the deaths of Gurdip Singh Chaggar in Southall (1976) and Altab Ali in London’s East End (1978). This led to the establishment of Asian Youth Movement (AYM) to defend communities from racist attacks. The AYMs also campaigned against racism in education, the workplace and in immigration laws (see: 'Families divided').

AYMs were inspired by the American Black Power movement, as well as by anti-colonial struggles in India and Africa(see 'Darcus Howe'). There were a number of ideas that AYMs adopted from the Black Power struggle: self-reliance, pride in oneself, the importance of self-defence training and the idea that a black person should never criticise another black person in public. The AYMs adopted a unified black political identity and used the symbol of the black power fist on their literature to suggest the idea of African and Asian unity against racism.

‘Kala Tara’ which means Black Star in Urdu, Hindi and Punjabi is another way AYMs expressed their identification with a political blackness. National liberation struggles, including the independence struggles of the Indian subcontinent, also provided AYMs with inspiration, as they provided examples of victories achieved by fighting against oppression. The injustices of apartheid in South Africa, as well as the success of the Zimbabwean struggle for independence in 1979, also inspired youth in Britain to fight against the racism they experienced. After the murder of Altab Ali in London’s East End in 1978, the AYM adopted slogans from the children of Soweto in South Africa, declaring on their leaflets: ‘Don’t mourn, organise’. This suggests the AYM saw the struggle against racism as an international one. The concept of political blackness offered an idea of this unity.In 1981 there were rising levels of racist attacks on the African, Caribbean and the South Asian communities in Britain. In March 1981 a fire broke out at a sixteenth birthday party for an Afro-Caribbean teenager in New Cross, leading to the death of 13 children. At the time it was believed that the house was fire-bombed in an attack. Neither the Queen nor the Prime Minister sent condolences to the families involved, exacerbating the feeling of isolation amongst black people. On 2 July 1981, Parveen Khan and her three children died in the East End of London after petrol was poured through her letter box. The threat of racist attacks on innocent people was feared across the country.

Photo of protesters and memorial to the 13 children who died in the New Cross fire, southeast London, 1981. (Courtesy of Homer Sykes)

Self-help and collective resistance: the Bradford 12 Defence Campaign

This campaign poster featured in the main source (see top of page) was produced by the Bradford 12 Defence Campaign. On 11 July 1981, members of the United Black Youth League (a splinter group from the Asian Youth Movement) heard rumours that British fascists were planning to march in Bradford. Given the rising levels of racist attacks, as outlined above, the United Black Youth League took rumours of the fascist march seriously and made petrol bombs (which they never used) to defend their community. The twelve members of United Black Youth League involved argued that they had made the petrol bombs in self-defence but, as the fascist march didn’t take place in Bradford, they were never used. Despite this, the twelve members of the United Black Youth League were charged with ‘conspiracy to cause explosives and endanger lives’. Through an active campaign and with supportive lawyers, they were eventually acquitted.

The campaign slogan ‘until the twelve are free, we are all imprisoned’ illustrates the way in which the campaign for the defence felt that the arrest of these men was an injustice to the black community as a whole. The influence of the Black Power and Civil Rights movements on the campaign to defend the Bradford 12 can be seen through the graphic of a dark-skinned and lighter-skinned fist, where both fists have been restrained by barbed wire. By depicting two fists, rather than one, the image gives the feeling of a collective struggle. This was an important point for the campaign, which wanted to express the sense of a community injustice.

Sources such as this defence campaign poster enable us to understand how migrant communities saw themselves and provide us with understanding of the identities they created. The men known as the Bradford 12 came from a variety of Asian backgrounds including Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Christian. These men had been drawn to campaign together by the shared experience of racism. They campaigned lawfully for over five years to expose police racism as well as the racism of immigration laws. This long history of lawful struggle can be seen by looking at the people who supported the campaign. These people included Anwar Ditta and Pat Wall, President of Bradford Trades Council and later MP for Bradford North.

Policing racism: trial, evidence and jury

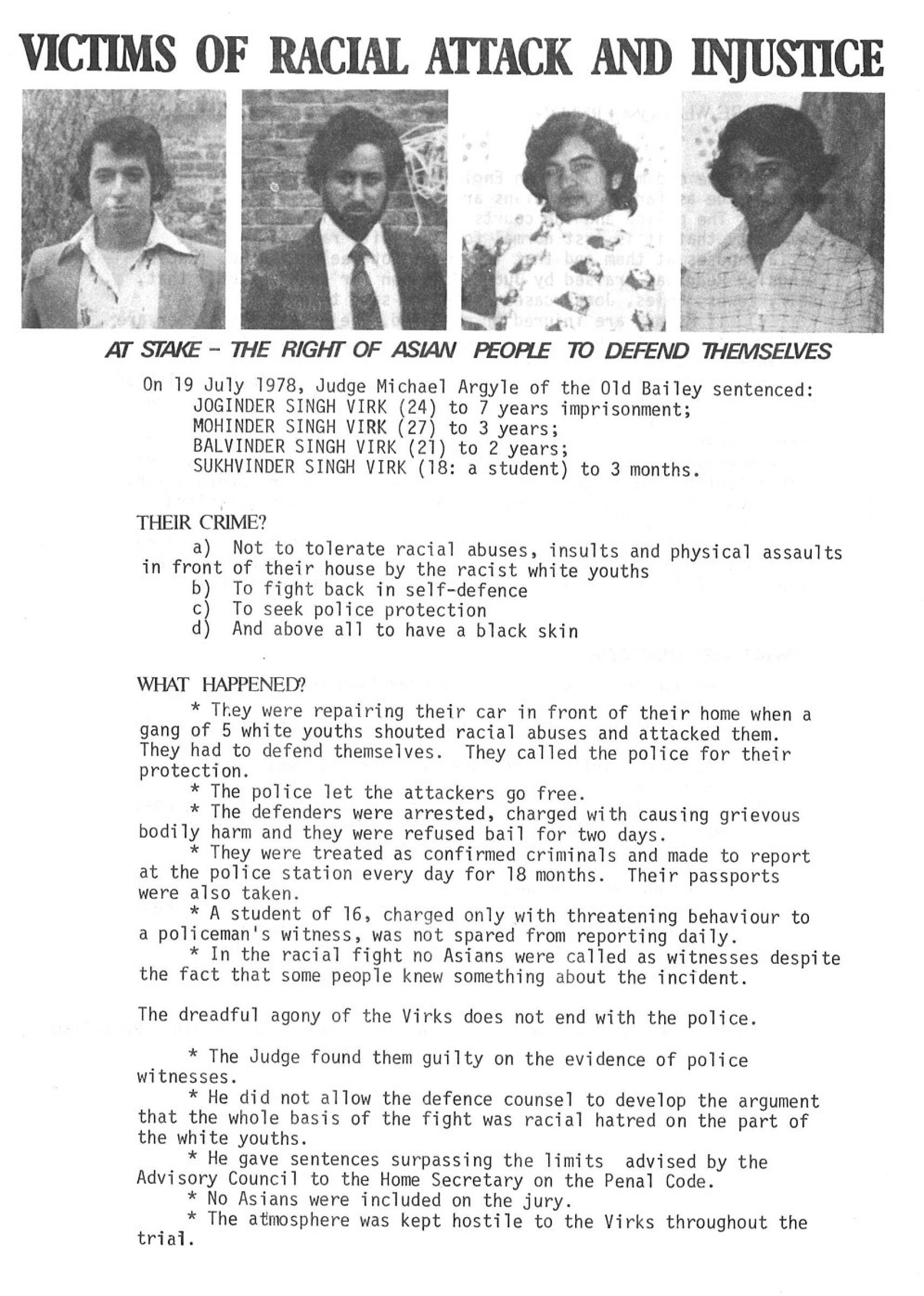

The Bradford 12 felt forced to take the action they did in 1981 in order to defend their community because, in the five years leading up to the rumoured fascist march in Bradford, the police had failed to respond adequately to racist attacks and had harassed young Asian and Afro-Caribbean men when they called for help. The case of the Virk brothers from 1978 makes this clear:

Campaign leaflet for the Virk brothers. (Courtesy of the Black History Collection, Institute of Race Relations)

During the Bradford 12 trial, evidence was given in court which exposed one local Detective Inspector, Holland, as saying that there was no such thing as racist violence and arguing that ‘Police officers must be prejudiced and discriminatory to do their job’. The police’s fabrication of evidence against the Bradford 12 was also brought to light through the construction of witness statements from the 12 defendants. During the trial it was clear that Special Branch had been involved in the arrest and interrogation of the young men.

The experience of the Bradford 12 mirrored the experience of Afro-Caribbean activists at The Mangrove Café in Notting Hill in 1970 (see: Darcus Howe). Patrons of the café were harassed by the Police and Special Branch, who were intent on destroying the development of a Black Power movement in the UK. When Black Power groups in Notting Hill organised a demonstration in defence of their community in 1970 they were charged with incitement to riot in a case that became known as The Mangrove 9. In court, two of the nine chose to defend themselves, in order to expose the political nature of the trial and the brutality of policing in Notting Hill. They also challenged the make-up of the jury, arguing that in law they had the right to be judged by a jury of their peers and demanded that they should be judged by a black jury.

The Bradford 12 learnt from the experience of the Mangrove 9. One leading defendant in the Bradford 12 case, Tariq Mehmood Ali, chose to represent himself. Also, just as in the case of the Mangrove 9 the Bradford 12 challenged the make-up of the jury to try to ensure a jury that was not racist and which offered some black representation. It took until 1997, following an official inquiry into the death of Stephen Lawrence, a black teenager from London, for institutional racism to be officially recognised (see the Macpherson report (1999) for more information).

In defending themselves the young men and the Bradford Defence campaign had to struggle against the racism of the media, which sensationalised the story of the Bradford 12 and which favoured police accounts of events. These police reports were later disproved in court. Media headlines such as ‘Black Gang in Plot to Bomb Police’ and ‘Petrol Bombs: Ready for Riot’, framed the activity of the Bradford 12 as criminal. This ‘trial by media’ of black people can also be seen in media coverage of many recent events and highlights the strained relationship between the police and black communities. For example, the unsubstantiated picture of Shiji Lapite as a drug pusher and as violent after his death at the hands of the police in 1995 served to discredit him as a figure of sympathy.

Collective campaigning

The acquittal of the Bradford 12 helped to enshrine in law the right of a community to defend itself. Previously the law had only been used to argue for individuals' rights to defend themselves. The campaign for the Bradford 12 included hundreds of organisations – community groups, trade unions, feminist organisations, student organisations, bookshops, Labour Party branches, national liberation and religious organisations – highlighting the levels of integration and participation by the community in wider networks. It also indicated the possibilities of diverse communities working together for justice and a better world.

This migration story of a campaign for justice is just one of many examples of migrant activism on this website.

Students should be encouraged to find and explore other stories of migrant activism on the site and to compare and contrast a handful of case studies. Students should be asked to think about similarities and differences between:

- the causes of different campaigns for justice

- the people who led the campaigns

- how the media responded to these campaigns

- what the role and response of the British government was

- what, if anything, the campaigning achieved

- The Bradford 12 Campaign is also an example of 'collective campaigning'. Why might a campaign for justice appeal to different groups - migrants and non-migrants? Has collective campaigning for justice historically been successful? If yes, or no, why?

- Why might migrants in Britain be interested in campaigning for justice on a global, not just local, level? Where can we find other examples on this website of migrants standing up for international causes such as anti-racism and anti-colonialism?

Students might also be interested to further explore the historical role of South Asia and South Asians in the development of the textile industry in Yorkshire and Lancashire.