Making peace: Scandinavian migrants and King Alfred's 'fyrd'

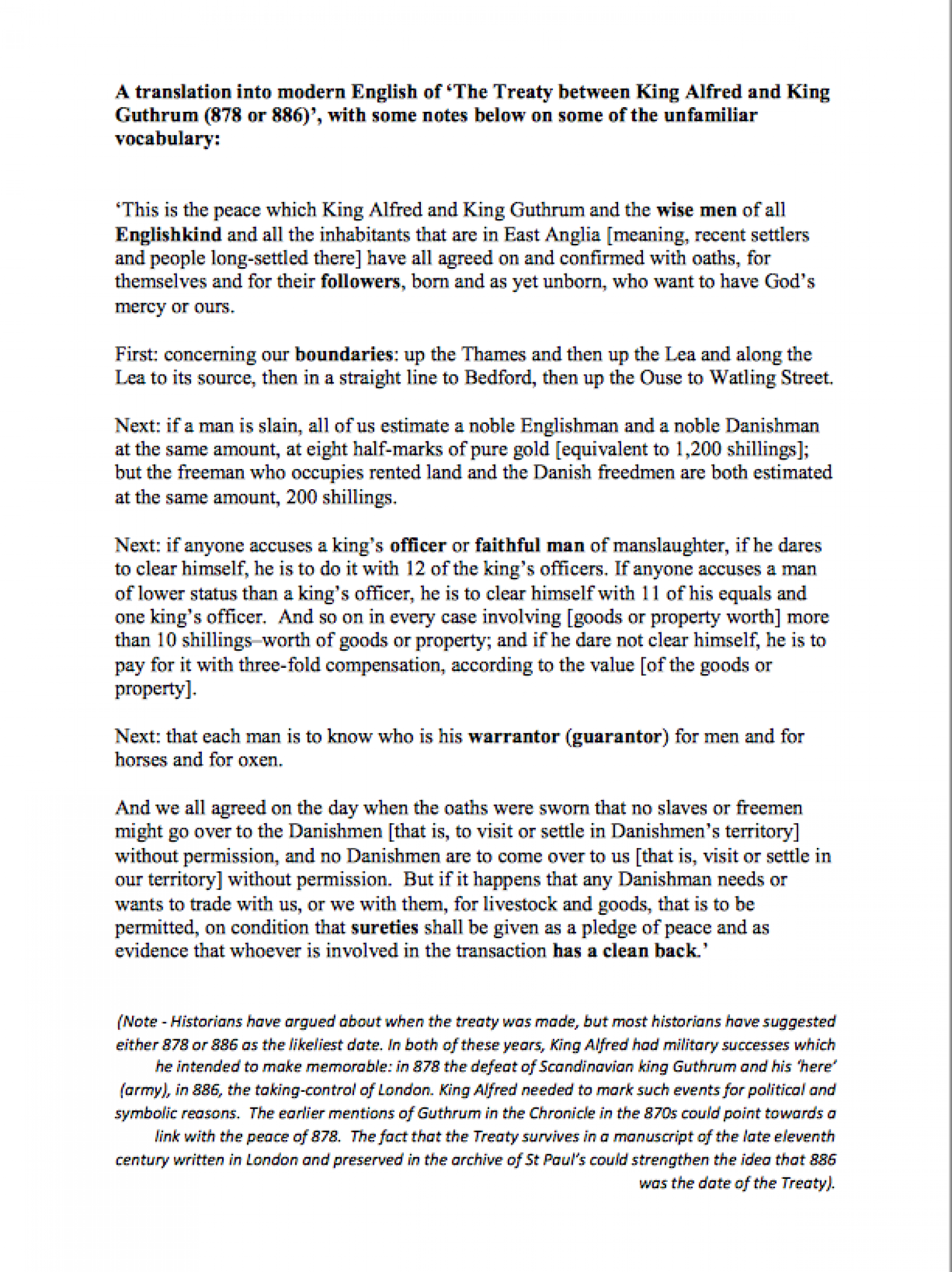

This map illustrates how the boundary in the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum appeared in the landscape. This boundary can be seen through evidence of place-names of Scandinavian settlement. Interestingly, hundreds of place-names ending in ‘-by’ can be found on Guthrum’s side of the boundary, and hardly any at all on Alfred’s side.

(Source information: the map above is based on A.H. Smith’s map using Early English Place-Name Society data and has been provided courtesy of Dr Jayne Carroll, University of Nottingham, and Professor Joanna Story, University of Leicester)

Scandinavians in England

From the late eighth century, Scandinavian raids on Scotland, Ireland, and England began to be recorded. At first these raids were very few, but from the 830s they became more frequent and from the 860s were serious. The migrants came mainly from Denmark and southern Sweden, which was ruled by Danish kings in the ninth century. Most scholars don’t think this was a migration caused by push factors like overpopulation at the source, but rather by pull factors such as the availability of high-value moveables in the British Isles and on the continent, especially in what is now northern France and Belgium. The Scandinavian migrants were chiefs with followings, sometimes of hundreds of men. They arrived in eastern England by boat, then got horses, and using Roman roads, raided on land.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

In the late eighth and ninth centuries, Scandinavians were treated by some chroniclers and letter-writers, and especially by theologians, as scourges sent by God to punish sinful Anglo-Saxons and Irish and, across the Channel, Franks (people in lands now inhabited by French, Dutch, and Germans). Scandinavians were, to use today’s phrase, ‘othered’, treated as aliens, as bloodthirsty and pagan. In the eighteenth century, the Vikings' migrations to England were treated in a similar way, which could be summed up in two words: ‘rape’ and ‘pillage’. Modern historians remained convinced by this story of violent Scandinavian invaders until the 1960s, when the established historical narrative about Scandinavian migration came under critical examination. Nowadays archaeologists and scholars of language, as well as historians, have uncovered other stories to tell about Scandinavian migration to Britain. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is an example of a historical source which tells an alternative story – not one of ‘rape’ and ‘pillage’, but one of Scandinavian assimilation.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was commissioned by King Alfred (871-99), and the earliest manuscript may well date to his reign. The text was compiled at his court and other copies were spread to major churches from these. It was unique among early medieval chronicles in that it was written in Old English, which was the language of every day speech (the vernacular), rather than Latin which was the language of the Church and which fewer people could understand. It contains information from earlier centuries – the first annal describes events in 60BC: 'Julius Caesar came to Britain', but really it starts in the year 1 AD when 'Christ was born', and goes on, with lots of gaps, providing a continuous record up to 1154. The earliest manuscript of the Chronicle dates from the 890s and its compilation was made at the court of King Alfred (871-899). It can be considered the biggest continuous historical document in medieval Europe.

Language and migration: from Old English to modern English

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle was written in Old English. Old English is basically a Germanic language, which is close to other Germanic languages like Old High German (where the earliest texts date from the ninth century) and Old Saxon. Old English is also close to the oldest know version of Scandinavian languages, for example, Old Norse. What is exceptional about Old English is that it was used to write laws, types of legal documents and quite a remarkable body of literature including poetry – including the poem Beowulf. From 43 AD, Roman settlers had introduced Latin speakers to the province of Britannia, where a variety of Celtic languages were spoken. Interestingly Latin didn’t survive the settlement of Anglo-Saxons in the fifth and sixth centuries. When missionaries arrived from Rome to preach Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons round about the year 600, they needed interpreters who spoke Old English. Germanic languages were more or less mutually understandable, which later on, in the ninth century, made settlement of Danes among Anglo-Saxons easier than settlement in northern France where in the ninth and tenth centuries the locals spoke a version of Old French derived from Latin.

The English language as it is spoken today is basically Old English with a large inclusion of Latin-based/Romance words. So our word ‘seldom’ (modern German ‘selten’) is a Germanic word, and its Latinate equivalent is ‘rarely’ (from ‘rarus’, rare). The reason the English language is so big – which any comparison between a dictionary of English and any other modern European language will show – is that it is an amalgam of two quite different languages, which occurred when the Normans (French-speakers today) conquered England in 1066. But if we look at what the English people were speaking in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries you will easily see that the Old English base was everywhere (in a form we call 'Middle English'), and that it was more English than French.

Scandinavian migration in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle briefly mentions the story of Scandinavians, mostly Danes, settling in England in the reign of King Alfred (871-899). These groups, referred to as ‘wicenga’ (the English word 'Vikings' actually dates from the eighteenth century), are only mentioned three times in the Chronicle – once in an entry for 878, and in two other entries for 884. The Chronicle does not say what, if anything, was special or different about these Scandinavian arrivals.

The author of this part of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was no hysterical theologian. His story was mostly a plain unvarnished one with a lot of nouns and verbs, and not many adjectives and adverbs. When Scandinavians entered his story, the chronicler’s tone does not change much. The Scandinavians were identified at the time by the Old English word ‘here’ (army) which was defined in Anglo-Saxon legal language as a group of ’30 men or more’. A ‘here’ could be quite small, but when several ‘armies’ combined, they could take on Alfred’s army, for which the Chronicle’s author consistently uses the word ‘fyrd’ ('big army'). A ‘big army’ could take control of a large area and its Anglo-Saxon population. These two distinct words, 'here' and 'fyrd', made it easy to see what is going on.

Making peace: the treaty between King Alfred and King Guthrum

Danes sometimes attacked and left with their loot. Sometimes they made peace with the locals and decided to settle (in Old English word is ‘saeton’). In the years between 871 and 886, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions eight occasions when ‘a peace was made’. On one occasion ‘The Treaty between Alfred and Guthrum’ was drawn up (see below). Like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle itself, this treaty was written in Old English, the language of every day speech, not in Latin which was the formal language of the Church.

Below is a translation into modern English of ‘The Treaty between King Alfred and King Guthrum (878 or 886)’, with some notes on some of the unfamiliar vocabulary:

PDF - modern English translation of ‘The Treaty between King Alfred and King Guthrum (878 or 886)’

In 875 Guthrum was one of three Scandinavian kings who, reports the Chronicle, came to Cambridge ‘and saeton thaer an gear’ (‘and settled there for one year’). In midwinter 877 Guthrum and his ‘here’ (army) moved to Chippenham in Wiltshire, ‘rode over Wessex and settled it’. At Edington in May 878, King Alfred and his ‘fyrd’ defeated Guthrum’s ‘here’, which fled back to Chippenham. After this, a peace was made, which involved Guthrum being baptized as Christian along with his 29 ‘weorthuste’ (worthiest) men. At the baptism, King Alfred stood as Guthrum’s godfather.

In 879, Guthrum’s ‘here’ went to East Anglia and settled. In 885, the Chronicle reports that the ‘here’ in East Anglia broke the peace, however, and in 886 King Alfred is reported to have occupied London ‘and him all Angelcyn to cirde’ (‘and all Englishkind turned to him’). The next and final mention of Guthrum in the Chronicle is his death.

The treaty as a story of assimilation: shared institutions, values, customs

The opening section of the treaty between Alfred and Guthrum establishes a sort of equal status between two kings, and their two peoples, ‘Englishkind’ meaning the Anglo-Saxons in Wessex on the one hand, and the ‘inhabitants of East Anglia’ under Guthrum on the other. Danish migrants had settled and assimilated with the locals in East Anglia and were already being treated equally. This suggests that the peace established by the treaty stood a good chance of sticking because the ‘English’ and ‘Danes’ already shared many ideas, institutions, and legal and social practices.

Becoming Christian seems not to have been a difficult process for Guthrum and his chief men. Once settled in East Anglia in 879, the king minted coins using his Christian name ‘Athelstan’. In areas of Danish settlement in England, archaeological evidence shows Danish settlers quickly taking up Anglo-Saxon burial customs and adapting to Anglo-Saxon styles. Intermarriage, and the borrowing of names or name-elements for people and places seem to have raised no major problems. ‘Grimston’ for instance is a hybrid name, the first bit Danish, the second English.

Both Alfred and Guthrum were kings, each had ‘gingran’, followers on whose loyalty they relied and for whose well-being they took responsibility. Their peace treaty was thus confirmed by oaths ‘for themselves and for their followers’. The standard modern English of ‘gingran’ is ‘subjects’, but this is misleading, because the bond between king and follower at this time included a key element of mutual regard and mutual obligation, of loyalty chosen rather than enforced.

Both kings and both populations understood ‘boundaries’ and, after decades of comings and goings, Danes shared with the English ideas of space, and of how boundaries followed rivers and roads. Interestingly, hundreds of place-names ending in ‘-by’ can be found on Guthrum’s side of the boundary, and hardly any at all on Alfred’s side. The boundary followed existing settlement, it seems, but settlement itself followed existing markers in the landscape (see map above).

The treaty also suggests that both English and Danes agreed that killing someone was a wrong that had to be atoned for and compensated for. English and Danes shared ideas about how to stop feuds, about social differences between noblemen and freemen, about how an accused man could clear himself, and about the equivalence of English freemen (who owed tribute, or rent, on their land) and Danish freedmen. Both kings had officers to organise local agreements involving money paid by killers and their kin to the families of the slain.

Within both groups, relations between lords and lesser men, patrons and clients, were well understood and English and Danes as distinct groups agreed to buy and sell among themselves, English with English, Dane with Dane. Men of wealth and standing provided guarantees for ensuring that their dependents played fair. For English and Danes, rules of justice were to be alike.

Finally, relations between the English and Danes were settled in the Treaty. Slaves and freemen were to be able to move across the land boundaries in each case, provided they had the relevant king’s permission. The voice of King Alfred is clear in the phrase ‘heora and ūs’ (‘them and us’). The word ‘here’ had eventually lost the sense of ‘army’ and come to mean ‘Danes’. This clause was not about traitors or defectors, but about mutual visiting and cross-boundary settling being permitted, and even encouraged. English and Danes, if they wanted to, were to be able to trade with each other, so long as arrangements were in place to help handle and police transactions.

The treaty itself, expressed in an Old English language that was distinct from that of the Danes, yet could be understood by them, provides the best evidence that Alfred and Guthrum, English and Danes, were the same in many ways – they sounded ‘gelicena’ (alike) – and unlike the stories later told about Danes, were able to live together in peace.

The photo above shows an Old English inscription over the arch of the south porticus at St Mary's Parish Church, Breamore, Hampshire (Courtesy of the Rector and Churchwardens of the Parish of Breamore). The modern English translation of the inscription is: ‘Here is manifested the Covenant to thee’ (The reference is to Jeremiah 31: 33, in the translation in the New English Bible). 'This is the covenant which I will make with Israel after those days, says the Lord; I will set my law within them and write it on their hearts; I will become their God and they shall become my people’ (St Paul picks this up in Hebrews 8: 10). The idea of a covenant, or agreement, between God and his chosen the people is fundamental to Judaism and Christianity.

- This source and the source on Anglo-Saxon invaders share several common elements. If you have not yet done so, read 'Anglo-Saxon Invasion and the Beginning of the English'. How are the stories about these two invading armies (Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxons) similar? How do they differ?

- Why might the tales told about Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians have changed over time?

- One of the major tasks of historians is to return to and question ideas that are held in their time period. What methods can historians use to prove their findings are accurate, even if they go against commonly held beliefs?