Building Italian communities: caterers, industrial recruits and professionals

‘Pure Ices’ Ice Cream Cart in a London Park, c.1910 (Courtesy of La Voce degli Italiani)

By the date this photograph was taken, the Italian ice cream industry in London was well organised. The main producers, located in Clerkenwell, all had their own territories and pitches to which ice cream carts and wagons were horse-drawn early in the morning for a day’s trading. The ice cream was kept in zinc containers (as seen in the photograph behind the girl’s head) and extra supplies were brought from the manufacturing base, often a domestic kitchen, as required. Earlier public concerns over hygiene and ‘licking glasses’ used to serve ice cream had been overcome with the introduction of the cone and wafer, kept in a tin as seen on the counter. The lady in the photograph is wearing Ciociara costume, indicating her origin in the Frosinone area of Italy. Her apron is an Italian flag and the Union Jack is hanging at the front of the cart.

Rapid growth: 1880s to the First World War

From the 1880s, the Italian presence in Britain grew rapidly. Between 1891 and 1901 the number of Italian-born people more than doubled, rising from 11,000 to over 24,000, with over half located in London. These British census figures, however, do not include those born in Britain to Italian parents; the actual size of the Italian community would have been much greater. Due to the Aliens Act of 1905 (see: Jewish immigration and the Aliens Act), there was little further expansion of the Italian-born population, which rose only by 1,000 between 1901 and 1911. In overall terms, during this period only a small proportion of emigrants from Italy arrived and settled in Britain. The vast majority were destined for the United States, Argentina and Brazil as well as other European countries.

By this period, Italian communities in Britain’s cities were well established. Italians clustered in places like Clerkenwell in London, Ancoats in Manchester, West Bar in Sheffield and Grass Market in Edinburgh. A second Italian neighbourhood formed in London, in Soho, with origins primarily in the northern Italian regions of Piemonte and Lombardia.

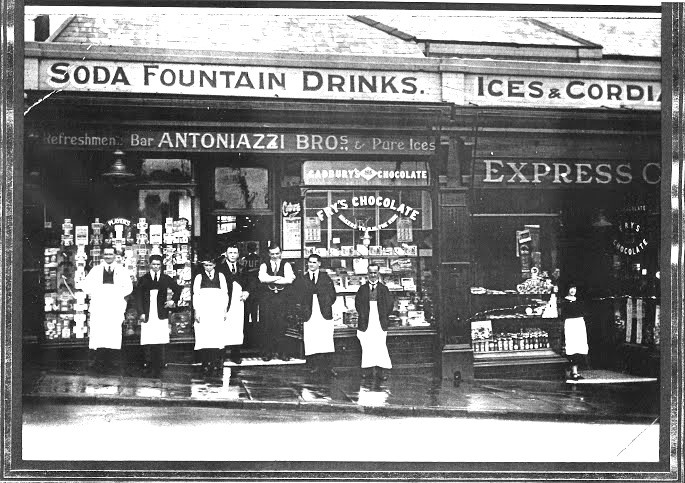

Growth in numbers and progression of the catering industry were supported by ‘chain migration’ of relatives and friends from Italy. Links were established between small towns and villages in Italy and towns and cities in Britain. For example, migrants from Barga (Lucca province) settled predominantly in Glasgow and Paisley where they formed the largest contingent of Italians. By 1910, one successful entrepreneur or padrone, Leopoldo Giuliani, owned twenty shops and had interests in at least sixty. In order to run and staff his shops, he brought over many youths from Barga who hoped to open their own business one day. Many succeeded, and so the chain migration continued.

In 1915, when Italy joined the First World War, 8,500 Italian men returned to Italy to serve their country. Unlike during the Second World War, Italy and Britain were allies in the Great War and Italians living in Britain also served in the British armed forces.

Interwar Britain: migration control and the rise of fascism

During the interwar years, there was little Italian migration to Britain, for two reasons. First, Britain’s Aliens Registration Act of 1919 and Aliens Order of 1920 restricted immigration by requiring ‘alien’ migrants to be in possession of pre-arranged work permits issued by the Ministry of Labour. Immigrants were also compelled to register with the police. Second, the Fascist Party in Italy passed laws limiting emigration and restricting internal migration within Italy. Between 1920 and 1940, the Italian-born community in Britain remained at around 25,000. Of this number, 50% lived in London, just over 20% in Scotland, less than 10% in Wales and 20% in the rest of England.

By the 1920s and 1930s, Italians had consolidated their niche activity. Almost every town hosted at least one Italian family in ice cream or fish and chips. In most cities, Italian shops were located on main roads and families lived above or beside their business. Lucrative Italian enterprises were located in popular seaside resorts, for example, along the south coast or on the Thames and Clyde estuaries. Some Soho Italians had also opened restaurants while others had climbed the ranks to become headwaiters and chefs at prestigious British venues.

Despite their economic success, Italians experienced prejudice, marginalisation and social isolation. Their ‘otherness’ was based on their perceived inferiority, appearance, Catholic religion, language and cultural traditions.

An important development in this period was the growth of fascism. Through his Italian ambassadors, Mussolini courted Italians living abroad in the hope of expanding Italy’s influence. One of the first fasci (Italian fascist sections) outside Italy was established in London in 1921. Other fascist clubs opened in Manchester, Liverpool, Edinburgh and Glasgow. By the late 1930s, the fasci controlled not only political but all associational and social activity within the Italian community in Britain. As the Second World War loomed, British security services watched closely, trying to assess the implications for national security of the potential ‘enemy within’.

'Divided loyalties’: British Italians and the Second World War

On 10th June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain. A night of anti-Italian street rioting followed and Italian shops were smashed up and looted, although few Italians were attacked. Churchill’s edict to “collar the lot” led to the arrest and internment, mainly on the Isle of Man, of Italian males between the ages of 17 and 60 who had less than 20 years residence in Britain. It was, however, difficult for British authorities to disentangle Italians over 60, British-born Italians, naturalised British subjects, residents in Britain of more than 20 years, Italian diplomats and anti-fascists. The so-called most ‘dangerous characters’ on MI5 lists, were to be deported.

The British ship, Arandora Star, sailed from Liverpool on 2nd July 1940 bound for Canada carrying an unsorted mixture of 712 Italian internees. She was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat off the Irish coast. 446 Italian men were drowned. The loss of life greatly affected Italians in Britain, as well as families and communities in Italy. For example, the small Welsh Italian community lost 53 men, originally from Bardi (Parma province). It was not until much later, in the 2000s, that the tragedy was publicly acknowledged when Arandora Star monuments and memorials were established in Glasgow, Cardiff, Liverpool and Middlesbrough and at St Peter’s Italian church in London.

For Italians in Britain, the wartime experience sometimes caused fragmentation and stress within families due to ‘divided loyalties’. British-born sons of Italian internees often served in the British armed forces. Yet others, unable to contemplate fighting against Italy, enlisted in a non-combative ‘pioneer corps’ of the British army. For women and younger children, wartime circumstances also proved testing as Italian families were forcibly moved away from their homes and businesses if located in ‘restricted zones’.

‘Mass’ migration and post-war recruitment schemes: Italian settlement 1949 to 1979

After the war, ‘bulk’ recruitment schemes brought thousands of Italians to Britain from the southern Italian regions of Campania, Sicily, Calabria, Molise, Puglia and Basilicata. This migration was driven by strong push factors, including war devastation, population growth, inefficient agriculture and an end to pre-war emigration restrictions. There were also ‘pull’ factors. In Britain, high demand for labour shaped formal recruitment schemes between the Ministry of Labour and its Italian counterpart.

The 1950s and 1960s witnessed the first ‘mass’ immigration of Italians who came, mostly to England, on mining, steel, tinplate, brick making and other employment contracts. By 1971, the number of Italian-born people enumerated in the British census reached 109,000. Italian sources, which include British-born Italians, recorded 213,500 in 1972. It is perhaps also worth noting that movement from the south of Italy in this period was not only directed towards Britain. Southern Italians also migrated to the industrial regions of northern Italy and to the growing economies of other European countries.

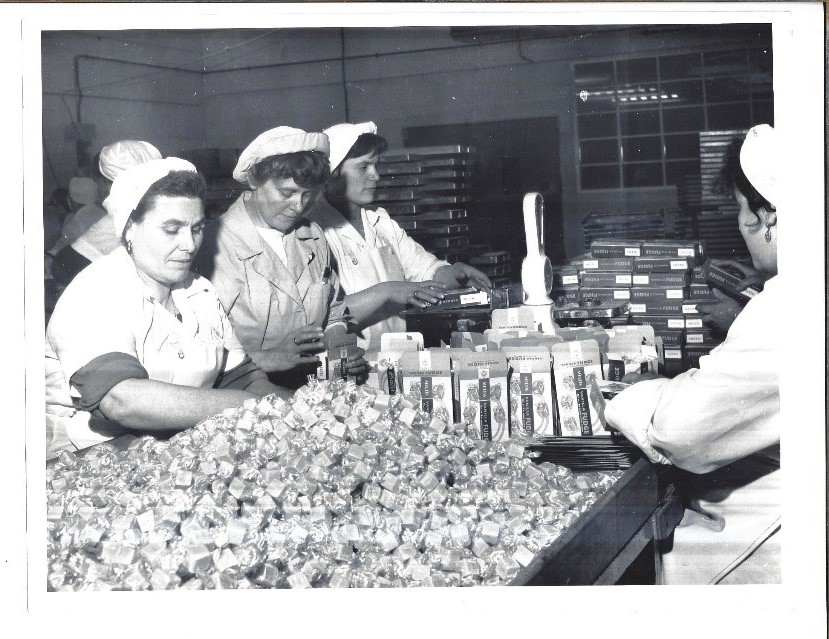

The first Italians to arrive on post-war recruitment schemes were 2,000 single, young women on four-year contracts for textile, rubber and ceramic factories in central and northern England. Whilst 2,500 Italians recruited for coal mining had to be sent back due to resistance from British miners’ unions, the most successful sector of industrial recruitment of Italian workers was in brickyards. As a result, between 1950 and 1960, Bedford and Peterborough experienced the formation of large, new, Italian communities. Initially, Italian brick workers were housed in basic hostels near their workplace. Adapting to their new industrial environment was challenging, as most of the men had previously been land workers. Women recruits soon joined the growing Italian workforce in Bedford, as factory employees in Tobler Meltis sweets and as hospital auxiliaries.

Tobler Meltis Sweet Factory, Bedford, 1975 (Courtesy of N. Verby from Terri Colpi (1991), Italians Forward: A Visual History of the Italian Community in Great Britain)

In towns like Bedford where their presence was significant in number, Italians formed residential clusters and experienced prejudice, for example, when trying to rent accommodation. The first generation of post-war arrivals never learned to speak English well and their social networks primarily comprised of fellow villagers or provincial compatriots. In Bedford, the main provinces of origin were Avellino, Campobasso and Agrigento in Sicily. By the 1960s, these migrants, had purchased their own houses, built an Italian church, founded clubs and associations, and opened the first shops selling Italian provisions.

Although bulk recruitment ended in the mid-1950s, four-year contracts were still available for many industries, including bricks. Numbers of Sicilians from the provinces of Agrigento and Caltanisetta, for example, built up in unskilled jobs in towns like Woking, Chertsey, Aylesbury and, notably, in the Lea Valley north of London where they took jobs as market gardeners, growing vegetables. These communities grew through chain migration. Employers appreciated the benefits of organising work permits for relatives and fellow villagers of already proven employees.

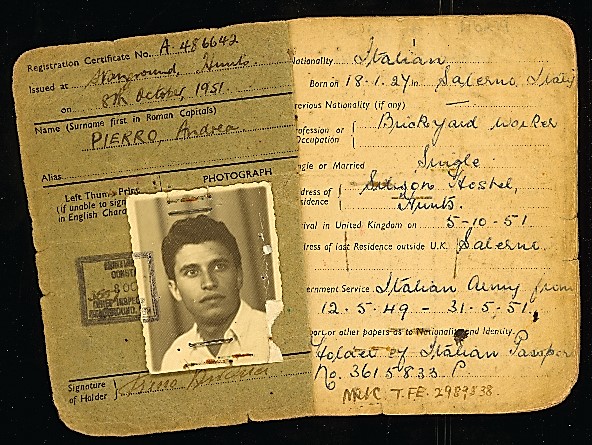

After the war, there was also a considerable reactivation of the historic chains of migration from central and northern Italy, from the long standing source provinces of Frosinone, Parma and Lucca. Such migrants arrived in the established centres of Italian migration such as London, Manchester, Scotland and Wales through work permits arranged by family or friends for the expanding catering and service industries. The first trattorie (trattorias) and Italian style espresso coffee bars were opened in the 1950s, with pizzerie (pizzerias) coming later in the 1960s. Work permits for other unfilled jobs could also be organised, for example, in domestic service or agriculture and, after four years, the migrant was free to move into employment in a family business or elsewhere. The Aliens Order of 1953 (an update of the Aliens Order of 1920) still required migrants to register at a local police station and keep an aliens booklet to document changes of address and employment.

By 1969, these migrations had come to an end and during the 1970s there was a net outflow of Italians from Britain. Demand for labour migrants especially had subsided and, after 10 - 20 years of working in Britain, many post-war migrants fulfilled their goal of returning to Italy. Most returned to their villages and invested their savings in land, small businesses and building villas. This ‘return migration’ continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s, but a small inward flow of students and young Italians occurred, especially after Britain’s accession to the European Economic Community in 1973. These migrants often came for temporary stays, to learn English or to study.

A new phase: Italian migration to Britain from 1980s onwards

In the 1980s, as the British economy and commercial links with Italy grew, a new phase in Italian immigration began. This period witnessed the arrival of Italian professionals - bankers, academics, engineers, scientists and artists. These migrants came from all regions of Italy, found work in many specialist fields and, although concentrated in London, dispersed nationally. Further European integration in 1993, job opportunities in Britain and cheap flights from the end of the decade, induced an ever increasing flow of Italian migrants.

By the 2000s, and especially after the 2008 global financial crisis, this new migration also encompassed jobless university graduates. From 2008 to 2013, Europe-wide recession and stagnation of the Italian economy combined with a lack of meritocracy, led to high levels of Italian youth unemployment (40% in 2014), and consequently extensive migration from Italy. These young Italian migrants, although well educated, lacked professional experience and in Britain many gravitated to the traditional and, by now exceptionally strong, Italian catering sector.

New Italian migrants have good English, are keen to integrate and experience little prejudice in ‘super-diverse’ Britain. Most describe themselves as ‘expats’ rather than ‘immigrants’. Hence, they perceive little commonality between themselves and the earlier Italian migrants to Britain.

British census figures show that, between 2001 and 2011, the Italian-born population in Britain increased by almost a third, from 107,000 to 141,000. Italian government figures, which include British-born Italians, reveal that between 2011 and 2017 the Italian community in Britain grew by 60% in just five years, from 187,000 to 300,000. Well over half are in London. However, by including non-registered Italians and all individuals of Italian heritage, official Italian consulate estimates put the community in Britain around 700, 000, making it the largest Italian presence in the world, outside Italy. Italians now form the third largest European group in Britain, after Polish and Romanian communities.

Italian culture and identity in Britain

Two centuries of Italian migration to Britain has ensured maintenance of Italian culture and identity both at the individual and community level. Alongside successful integration to British society, robust ties with Italy persist which are supported by extensive institutional structures. As well as a nationwide Italian consular network, there are Italian institutes of culture in London and Edinburgh, Italian churches in London, Bedford and Peterborough, Italian priests in Bradford, Birmingham and Woking, an Italian school in London, scores of active Italian associations, Italian centres and meeting places and numerous websites and social media platforms formed by the latest migrants.